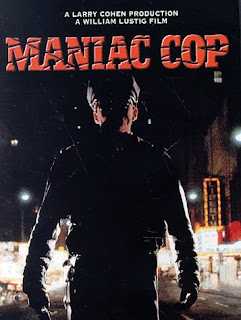

I've always wondered why the great Larry Cohen (The Stuff, It's Alive, Bone) chose not to direct Maniac Cop. His script fits perfectly into Cohen's gritty, grungy oeuvre. Nevertheless, director duties went to William Lustig (Maniac).

The film stars Tom Atkins ( Halloween 2), Bruce Campbell (Evil Dead), Robert Z'Dar (Tango and Cash) and Laurene Landon (Samurai Cop 2).

Z'Dar, the biggest chin in Hollywood, plays the eponymous maniac cop, back from the dead to take his odd revenge. Tom Atkins, playing largely Tom Atkins is the detective on the case. The maniac cuts a swath of seemingly random murders, and only Atkins thinks the killer could be a real cop.

Enter Bruce Campbell (the second biggest chin in Hollywood) playing Michael Moriarty in any other Cohen penned movie, as a hapless beat cop who is suspected of being the killer after his semi-estranged wife is murdered.

Landon plays the vice cop that Campbell is sleeping with behind his wife's back. She too joins the hunt for the hulking killer.

Maniac Cop is a bunch of stupid fun, if lacking in Cohen's normal social commentary. It's much less sleazy and gory than Lustig's Maniac, as well. It has some fun kills, solid B movie acting, and touch of wry humor.

It's a solid Sunday morning watch.

Zombies!!

In this discussion the first order of business is to define the sides in the ongoing fight over the question of the soul. As was stated earlier, there are three sides: Idealism, Materialism and Dualism. We will need to explore each of them separately.

Idealism

We will look at Idealism# simply so that we may dismiss it almost out of hand. The Idealist believes that there are only minds and thoughts created by minds. To make it clear, the Idealist denies that there are any material objects or physical beings in the whole of the universe. A cursory examination of the idealist philosophy reveals that it is largely absurd as well as being psychologically unsatisfying. Even if we were to ignore those two highly persuasive facts, we would still have to contend with the problem posed by temporal constancy. The idealist must believe that the chair that he sits in is not, in fact, a chair but rather merely an idea in his mind which he has mistaken for a material object in the shape of a chair. This seems barely on the outskirts of plausibility until we consider the following scenario: You enter a room and arrange the chairs in an odd configuration, then write down the precise location of each chair before exiting the room. An hour later a person that you have had no contact with then enters the room and writes down the location of each chair in the room. If the two of you come together and compare notes you will learn that you have observed the same configuration of chairs. If you have each only mistaken your own private thoughts for material objects shaped like chairs then it seems that you should observe different things. In this way Idealism knocks out its pins and collapses upon itself. It was never really taken seriously by anyone anyway and has few partisans. The other two sides in this battle have much more power behind them.

Materialism

Materialism holds that a person is an animal. We are, the materialist claims, merely material, physical beings. Nothing more and nothing less. The mind, the materialist says, is an effect of the physical brain. The materialist insists that there is no soul or spirit and that what we call ‘mind’ is merely a series of electrical and chemical reactions within that self same brain.

Dualism

The Dualist would agree with the materialist that man is a material being, a physical animal. But, the dualist claims, in addition to the physical components man also is possessed of a non-physical mind (spirit or soul works just as well here). The dualist says that it is this non-physical aspect that is responsible for consciousness, thought and our knack for ethical decision.

Those are the three sides in the mind-body discussion.

The Living Dead

George A. Romero is a film maker best known for his zombie genre movies. Romero’s Zombie films are: Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Land of the Dead and Diary of the Dead. These films all take place in a universe where humanity has been over run by a plague of flesh eating zombies. These zombies are previously dead humans that have been resurrected by some process that is never explained to the audience. In each film a small band of human survivors attempt to outlast or out fight the undead cannibals# that stalk them. The first two entries in the series# are both extraordinary entertainment and fascinating satire# but fail to reach the philosophical heights that the latter films would reach.

Day of the Dead features a zombie named Bub who is the subject of certain behavioral experiments. In the course of the film Bub demonstrates the ability to learn, to remember things from his past and to use objects (one is tempted to say tools, but that seems to miss the point of a phone in a world where there is no one left to talk to). Near the end of the film Bub even comes very close to speaking a word.

In Romero's follow up, Land of the Dead, the zombies evolve even further. In that film, the undead follow a leader, Big Daddy#. Big Daddy not only displays the ability to use tools, but transmits and teaches that ability to other zombies. The film culminates with an army of the undead marching on the last human city.

What then, does all of this have to do with souls?

It seems clear that learning, memory and choices are actions of the mind#. If zombies can learn, then they must have minds# (again, soul works just as well). The problem this causes for Dualism should be clear:

The Dualist believes that the soul (mind) is something non-physical which leaves the body at death. The zombies have died, and when that happened, the incorporeal part of them should have fled. When their bodies were re-animated, they should have become mindless automata. The Materialist suffers no such problem. The materialist claims (as we have discussed) that the mind is just a material function of the brain. As such, the re-animated zombie still possesses its brain, and so should be capable of thought (that these abilities are somehow diminished can be explained through the decay of brain tissue).

When these facts are considered, it seems manifestly clear that Romero’s Zombie films belong to the class of philosophical literature and that they fit cleanly on the materialist side of the mind body problem.

Bloodfest the Podcast

I’m Not There presents a variety of characters inspired by the real Dylan and several imagined ones, including a young boy riding the rails; a folk singer; an actor and an ageing Billy the Kid. Each section of the film has a different actor portraying an alternate universe version of the film’s subject.

Christian Bale, as Jack, has the duty of book ending Dylan’s career in a manner. Jack shows us the effect of change on our hero, portraying the counterfactual Dylan through both his conversion to electricity and Jesus. These two events both sent shockwaves through the fan community, and Bale perfectly exudes the sadness and rage that Dylan must have felt.

The late Heath Ledger plays Robbie, the actor chosen to play Jack in a biopic. Robbie is overwhelmed by sudden fame and seems to crumble under the pressure. Watching the film after Ledger’s untimely death it is impossible not to draw comparisons between the character and the actor. It becomes almost impossible to judge the performance on its own merits (Ledger’s other final role, as The Joker in Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight, does not suffer from the same problem, being pure fantasy).

Marcus Carl Franklin plays Woody Guthrie, a young man riding along with hobos and playing his guitar for anyone who will listen. Here Haynes has melded the outright lies Dylan told about his youth with his love of the great American troubadour Guthrie. Franklin, though only a child, shows some real depth and grace. A short cameo by the mighty Richie Havens nearly steals Franklins portion of the film at a first approximation, but on a second viewing it becomes clear that the most fascinating scene is a quiet one with Franklin sharing a meal with a family that has taken him in for a day.

Ben Winshaw portrays Arthur Rimbaud. Arthur is being questioned. We are given to feel that his interrogators may be government agents. We are a bit like Mr. Jones: There is something (sinister) going on here, but we don’t know what it is. Winshaw’s dialogue is largely inspired by Dylan’s frequent refusal to provide his interviewers with anything like a straight answer to even the simplest question. Ben Winshaw is unknown to me, but he has the face of a slightly malnourished cherub. His look and manner are similar to Dylan’s, but in a one off sort of way. It seems, at moments, like he is mimicking Kate Blanchett’s portrayal of Dylan. Given that we notice that Arthur is clearly younger than Jude, we are led in a strange, recursive loop as we try to untangle how these characters are related and how the performances are related.

Richard Gere rounds out the cast as Billy the Kid in repose. Gere has never been much of an actor, known primarily as a pretty boy now well past his sell by date. Here he manages to stretch beyond his usual range (helped greatly by the performance of a dog, which lends pathos). Gere gives us Billy the Kid as he ages (assuming that Henry McCarty wasn’t actually gunned down by Pat Garrett), living a quiet life out of the spotlight.

Any attempt to summarize or dissect the film’s plot would be futile, as this is largely a collection of vignettes chopped up and thrown together in William S. Burroughs cut-up style to create the illusion that a real story is being told. That doesn’t really matter though, as this film is more about style than substance. Haynes shifts visual styles with each character and sometimes changes narrative style mid scene. He cross-pollinates a Cinema Verite look, with documentary inspired graininess and smashes those up against a naturalistic looking American west, then slides into the surreal before dropping to his music video roots. None of this should work. The film should obviously knock the pins out from under itself and collapse. And yet, somehow it holds up. Possibly it is just the quality of the performances given by this fascinating cast. Perhaps it is our innate fascination with the subject. Maybe it’s the incredible soundtrack blowing the best of Dylan out the speakers. Whatever it is, I’m Not There works better than it should.

Haynes doesn’t manage to untangle the mystery of Bob Dylan. In fact, we are left with less understanding of the real man. Yet, for a couple of hours we are able to vanish into Dylan’s world, a world where buckets of tears fall from the sky, and maybe we can, finally, find shelter from the storm.

Comments

Post a Comment